Serin did not notice the sun had gone down again.

The light in the tower study was always the same now: tired candles guttering in iron brackets, the faint amber glow of charmed globes long past their prime, the grey smear of evening through the narrow window slit. Day and night had blurred into one long, ink-stained hour.

Pages covered the desk. Pages covered the chair beside the desk. Pages had colonized the floor, spilling in drifts around the legs of shelves that were themselves sagging under the weight of more pages.

Serin stared at the latest sheet, the ink still damp.

The Convergence of Liminal Topographies: A Taxonomy.

It said nothing else. No text, no argument, no spark. Just another impressive-sounding title, written in neat, controlled hand.

Serin set the quill down and realized, with a sudden hollow swing in their chest, that they did not know what they had meant to write under it.

The word “Convergence” had once meant something exciting. It had tasted like thunder on their tongue, like the edge of a discovered map. Now it was just one more stone in a long wall of words they no longer believed.

They dragged both hands over their face. Their fingers smelled of old ink and tallow.

“What was the question?” Serin whispered to the empty room.

The tower answered with creaks and the muffled sigh of the wind between stones.

Somewhere above, a book shifted on a shelf with a soft scrape. Dust sifted down in lazy spirals.

Serin ignored it. They forced their gaze back to the page and tried to drag up the thread of thought.

Thin places. Crossroads that didn’t fit on maps. Doors that only opened once.

They’d chased those ideas for years. Collected stories of vanishing roads and wayhouses that appeared only in storms. Interviewed travelers who swore they had drunk with strangers from other eras. Wound those accounts into theories fine enough to impress committees.

In all that time, with all those treatises and lectures and citations, the feeling underneath—the aching, childlike certainty that there had to be a place where lost people could go and rest—had been buried under footnotes.

“What did I want to know?” Serin asked the air, and this time their voice cracked.

A candle near the window guttered, flared—then went out completely.

The brief darkness that followed was deeper than it had any right to be.

Serin blinked, waiting for their eyes to adjust. The other candles still burned, but their light felt narrow and thin, as if something just beyond the circle of illumination had thickened.

Another sound from higher up in the room. A slow, grinding shift, as if a shelf that had not moved in years was suddenly reminded that gravity existed.

Serin frowned and half-rose from the chair.

“Not now,” they muttered, to the shelf or the tower or themselves, they weren’t sure. Fatigue hung from their limbs like chains. “Tomorrow. I’ll… I’ll fix it tomorrow.”

Something fell.

It was not the soft flutter of a single volume slipping from its place. It was the heavy, meaty thump of a book that had no business coming down from that height unless pushed by a determined hand.

It landed near Serin’s boots, rebounded once, and lay splayed open on the floor.

Serin stared at it for a few seconds, brain sluggish. Then they sighed.

“All right,” they said, and pushed themselves to their feet.

Their knees complained. Their spine popped. They shuffled around the desk, avoiding teetering stacks of paper with the unconscious grace of long practice.

The book that had fallen was an ugly thing: a bound miscellany of old lectures and committee notes, thick with marginalia. Its spine was cracked, its corners chewed. It lay open on a page that held nothing but an ink blot and the faint, ghostly impression of erased writing.

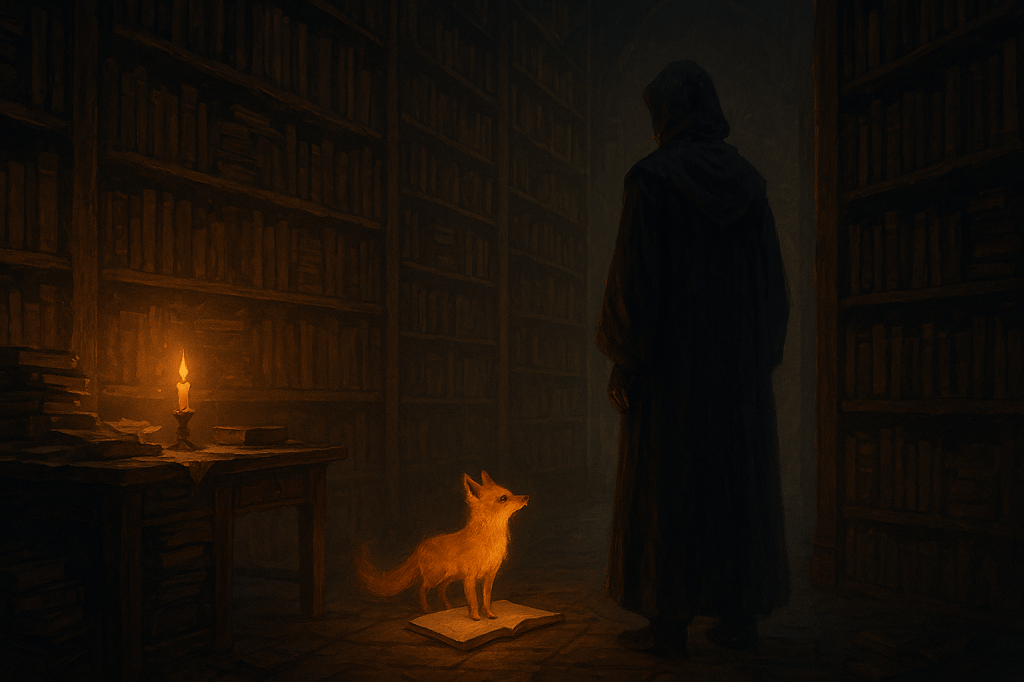

Beyond it, in the shadow beneath the nearest shelf, something watched Serin.

At first they thought it was just the way the candlelight hit the darkness—two glints like coins or drops of dew. Then the glints blinked.

Serin went very still.

From the deeper dark, a shape stepped forward: small, low to the ground, the size of a fox. Its fur was the color of autumn leaves and cinders, except that no fur should catch the light like that. It shimmered faintly, as if lit from within by a hidden lantern.

Long ears pricked forward. A fine-boned muzzle, whiskers catching light in silver filaments. A tail, full and sleek, the tip glowing brighter than the rest, like a coal banked in ash.

Serin’s breath hitched. Their mind went scrambling uselessly through catalogues of known spirits and illusions.

The creature tilted its head. In the reflected candlelight of its eyes, Serin saw their desk: papers, abandoned quill, cold tea, and—jutting out from a precarious stack—a battered little notebook with a cracked leather cover.

The fox’s gaze lingered on the notebook.

It did not speak. It did not make a sound at all. Its tail tip brightened, just enough to draw Serin’s eye, then dimmed.

Serin swallowed.

“You shouldn’t be here,” they said, more to see what the creature would do than from any belief that it would listen. “This tower is warded. The library—”

The fox stepped daintily over the fallen book, ignoring it completely. Its paws disturbed no dust. It walked right past Serin, crossing the floor with the casual, unhurried confidence of something that had been here before and would, with or without permission, be here again.

It leapt lightly onto the chair beside the desk, then onto the desk itself, where it threaded its way between stacks of pages without so much as stirring a crumb.

Serin’s heart pattered against their ribs. They followed on stiff legs.

“Careful,” they blurted, as the creature passed near a tower of notes balanced on the edge of the inkstand. “Those are— I mean, I spent—”

The fox ignored the warning. Of course it did. It had never asked to be included in Serin’s priorities.

It reached the battered notebook and paused. For a moment, its outline blurred; the inner light pulsed gently, like someone cupping a lamp and then slowly revealing it again.

Serin stood on the other side of the desk, pulse thudding, hands pressed flat to the wood as if to steady them.

The fox lowered its head and nudged the notebook. Not enough to send it flying—just enough to shift it by a finger-width, to make it undeniably the center of the scene.

Then it looked up at Serin.

Those eyes were not human. They were too clear, too old. But in them Serin saw a reflection that hurt: a younger version of themselves, ink-smudged and bright-eyed, clutching that very notebook like a treasure.

Serin let out a shaky breath and reached.

The leather was dry and cracked under their fingers. The little tie strap broke as soon as they pulled, but the book opened willingly.

The first page held a title written in an untidy hand that had never imagined a committee’s red ink:

Questions No One Has Answered Yet.

Serin’s throat tightened.

The pages beyond were full of scrawls and sketches. No elegant structure, no polished thesis. Just bursts:

- Why do the same stories appear in different lands?

- Where do lost roads go when they vanish?

- Is there a place where people who don’t fit anywhere else can rest?

- A drawing of a tavern at a crossroads, lanterns hanging from its eaves, tiny foxes playing in the yard. Above the door, something like a signboard, left unfinished, as if the younger Serin hadn’t decided what to call it yet.

The memory hit like sunlight through a long-shuttered window.

They had been young when they wrote these. An apprentice in a drafty dormitory, half-frozen fingers gripping a cheap quill, staying up by contraband candlelight to record every question that wouldn’t leave them alone. The world had felt wide and strange, full of holes where impossible light leaked through.

They had not been interested in tenure or reputation then. Only in finding that place—the one from the stories. The welcoming room between storms.

Now they were here, in a tower filled with proofs and procedures, and they could not even remember why the word “Convergence” had once made their heart race.

Serin’s eyes stung. They blinked hard, breath coming short.

“You…” They looked up at the fox. “Did you bring this? Did you—”

The fox had not moved. It sat with its front paws neatly together, tail wrapped around them, ears forward. The light inside it burned soft and steady.

It blinked once, slowly. Then it turned its head toward the shelves.

When Serin did not move, the fox hopped down, its paws silent on the desk, and—without knocking over a single page—leapt to the floor. It trotted toward the nearest aisle between towering bookcases, its glowing tail trailing a faint afterimage.

At the threshold of the aisle, it looked back over its shoulder.

Serin felt the invitation as clearly as if it had spoken.

Their gaze flicked back to the notebook. They hesitated only a moment before tucking it into the inside pocket of their robe, close to their chest.

Then, heart pounding in a way that had nothing to do with deadlines or appointments, they followed.

The aisle between the shelves was not especially long. It had never been especially long.

Now it stretched.

The further Serin walked, the more the world narrowed to the smell of parchment and ink, to the soft gleam of fox-light ahead. The tower walls fell away; the ceiling climbed until the shelves vanished into shadow.

They looked back once.

The study was still there, a warm square of light and cluttered safety. But it seemed small now, like a painting on distant stone, not a place one could easily step back into.

The fox trotted on.

Shelves loomed higher. Some of the books here were familiar: monographs Serin had read or cited, treatises that had occupied whole seasons of their life. Others were strange, bound in materials they did not recognize, titles in scripts that pricked at the edges of their memory.

They reached a junction where the aisle split in two.

Without slowing, the fox veered left.

Serin started after it—then stopped, struck by a peculiar detail on the right-hand path.

There, row upon row, were identical books. Same color, same size, same stamped lettering on every spine. Only the titles shifted:

The Convergence of Liminal Topographies: A Taxonomy.

The Convergence of Liminal Topographies: A Reappraisal.

The Convergence of Liminal Topographies: Collected Lectures.

Supplemental Addenda to the Convergence of Liminal Topographies.

And on, and on, and on.

Each spine bore Serin’s name, growing larger with each new variant, while the subtitles shrank into cramped, illegible script.

The nearest copy shuddered. Without any visible force, it slid from its place and fell at Serin’s feet, bouncing once on the floorboards that should have been stone.

The cover snapped open.

There was nothing inside.

Blank pages, edge to edge. Not even a publisher’s mark.

Serin felt sudden nausea. They backed away a step.

The fox had paused at the corner, looking back. The light in its fur dimmed, as if they had turned down the wick of an unseen lamp. It stood there, watching, until Serin tore their gaze from the empty book and stumbled after it.

The aisle twisted.

They passed another run of shelves, these labeled in a script that seemed to shift whenever Serin tried to read it: Impact Metrics, Committee Minutes, Grant Justifications. The books here were heavy as bricks. Some bore chains instead of titles.

Serin’s shoulders hunched.

They had thought they were walking away from that burden.

The fox’s path turned again, and suddenly the narrow corridor opened into a circular room Serin had never seen before.

It should not have existed inside the tower. The dimensions were wrong; the proportions made their skin prickle.

A round reading table stood in the middle, surrounded by shelves rising like the walls of a well. High above, no ceiling—just a dim haze.

Six chairs ringed the table.

Five of them were occupied.

Serin froze on the threshold, breath catching in their throat.

They were all Serin.

Nearest on the left sat a child, legs too short to comfortably reach the floor, boots scuffed and ink on their nose. Their hair stuck up in an unruly mess; their eyes burned with a feverish brightness. The battered notebook lay open in front of them, half full of sketches of crossroads and a tavern under strange stars, its name left blank.

Next to the child, an older apprentice version hunched over field notes, cloak still dusted with road grit, fingers tapping eagerly as if they could barely keep up with the stories spilling from their memory. A little wooden fox charm dangled from their belt.

Beside them, a young scholar in fresh robes argued with someone invisible across the table, hands slicing the air, eyes hard with the sharp-edged certainty of the newly published.

The fourth Serin was middle-aged, shoulders starting to stoop, ink stains ground into their cuffs, lips pressed thin. Letters of refusal and “regrets to inform” surrounded them like fallen leaves.

The fifth was the one Serin recognized too well: present-day, hollow-eyed, a smear of candle soot on one cheek, staring at a blank page under a title that had lost its meaning.

The sixth chair stood empty.

The fox walked into the room, paws soundless on the floor. It hopped onto the table with an ease that paid no mind to the ghost-selves seated there.

None of the other Serins looked up. They flickered, slightly transparent, like reflections in disturbed water.

The fox moved slowly around the circle.

It passed the older scholar, whose fingers trembled from too much coffee and too little sleep. The light under its fur dimmed as it went by, the air seeming to grow colder.

When it reached the youngest Serin—the child with the notebook—it paused.

The little Serin’s hand, holding a stub of a quill, hovered over the page. Their lips moved as they whispered words only they could hear. The notebook lay open to a drawing: a door with a lantern above it, and beside the door, the outline of a fox, hastily sketched but unmistakable.

The fox lowered its head and touched the drawn fox with the tip of its nose.

For a heartbeat, the ink lines glowed.

The child Serin looked up, eyes wide. For the first time, one of the echoes saw something beyond its own memory. Their gaze met the real Serin standing in the doorway.

Accusation. Longing. Disbelief. All of it flickered there at once.

Serin’s chest felt too small.

“I didn’t—” they rasped, though there was no breath to carry those words across time. “I just… I thought I had to… I had to make it respectable. Serious. No one listens if—”

The child’s mouth moved. Their voice did not reach Serin’s ears, but the shape of the words did.

Then why did you stop asking?

The air shuddered.

One by one, the other echoes blurred. The field scholar dissolved into a flurry of leaves, the ambitious lecturer into drifting pages, the middle-aged worrier into thin smoke. The present-day echo lingered longest, a hollow specter at the sixth chair, then folded inward and vanished.

The chairs sat empty.

Only the fox remained on the table, tail curled around its paws.

It looked at Serin.

For a long, ringing moment, nothing moved.

Then the shelves around the room shifted.

Labels seared themselves into being along their edges, changing even as Serin watched:

Published Works became Proof I Deserve to Exist.

Committee Decisions became Fear of Being Cast Out.

Field Notes became Lives I Chose Not to Stay With.

Questions became Why I Started.

Serin swayed where they stood. The notebook in their pocket felt like it weighed as much as the tower.

“I don’t want to be here anymore,” they whispered. “Not like this.”

The fox stood.

It padded to the edge of the table and leapt down, landing without a sound. As it walked toward Serin, its fur brightened, until the room seemed lit mostly by that inner glow. It brushed against Serin’s leg, the touch warm through the fabric of their robe.

For the first time in years, Serin felt something inside them loosen. Not entirely—there were still knots, still grief—but something gave.

The fox turned away and walked to the far side of the round room, where there had been only more shelves.

Now there was a doorway.

No—two.

The first stood to the left: a stout, perfectly ordinary door of dark wood, brass handle polished by imaginary hands. Above it, neatly carved, was a plaque:

TENURE & SECURITY.

Behind its frosted panes Serin saw the suggestion of a tidy office: a desk, a window, the vague movement of people who would ask the same questions, year after year. Everything was softened, safe, slightly blurred, as if the world beyond were wrapped in cotton.

The second “door” was nothing but a simple wooden frame standing alone. Beyond its threshold, there was no wall—only darkness pricked by a low, reddish light. The smell of woodsmoke drifted through, threaded with the savour of something cooking and the faint brightness of citrus and spice.

Somewhere in that unseen space, voices rose and fell. Laughter here, a murmur there—never quite distinct, as if heard through a wall of rain or across a long, echoing hall. It felt like overhearing a life Serin had not yet lived, stories circling a place their research had tried to describe but never quite reached.

The fox padded up to the plaque over the left-hand door.

It stretched, set one delicate forepaw on the word SECURITY, and dragged its claws across the carved letters.

They blackened at once. Cracked. Flaked away like burnt paper. The frosted glass behind them clouded, whatever lay beyond sinking into a dull, undifferentiated grey.

The fox dropped back to the floor and shook its paw once, as if flicking away ash.

Then it walked to the bare wooden frame and sat just inside the threshold, half its body swallowed by shadow, half outlined in that warm, unseen glow. Its tail-tip burned brighter, a small, steady star.

Serin let out a breath that bordered on a laugh and a sob at once.

“I’ve spent fifteen years chasing the safest answer to every question,” they said hoarsely. “And now you want me to walk into a door with no name.”

The fox did not nod. It did not speak.

It simply watched them and gave one slow, deliberate sweep of its tail against the frame, the gentle tap as clear as any answer.

Serin slid a hand into their robe and drew out the battered little notebook.

It felt smaller here. More honest.

They flipped to the last blank page.

The words came easier than they had on any title page in years:

Proposal: To find the place where lost paths meet, and to listen.

No methods. No committee-friendly phrasing. Just the old question, put back in its proper place.

They tore the page out and folded it once, twice, until it fit neatly in their palm. Then they tucked it into their inner pocket alongside all the earlier, messier questions.

The paper crinkled against their chest.

“All right,” Serin whispered. “No plaque. No guarantees.”

They stepped past the door marked TENURE & SECURITY without touching its handle.

The closer they came to the empty frame, the clearer the other scents became: damp stone after rain; smoke curling from some great unseen hearth; yeast and spice; metal and leather; a faint bite of something like apple and something like pine. It smelled like stories. It smelled, absurdly, like the little drawing in the notebook had been trying to remember.

On the very edge of the threshold, fear tightened around Serin’s ribs.

“What if I’m nothing, out there?” they asked the space between. “What if all I am without these books is… no one at all?”

The fox stood.

It pressed its shoulder firmly against Serin’s leg, not pushing, only grounding. The warmth of it bled through fabric and skin. For a moment, Serin could feel its heartbeat—a quick, sure rhythm, utterly unconcerned with committees or titles.

Then the fox stepped forward and passed through the frame.

For a heartbeat, the light inside its fur flared, filling the doorway with a glow like lanterns seen through mist. Shadows of beams, tables, hanging shapes—bottles, charms, a signboard with some small fox-shaped emblem—sketched themselves in the brightness and vanished again before they resolved.

Serin took a breath that tasted of smoke and unknown places, and followed.

The tower, the shelves, the circular room, the safe door with its half-burnt plaque—they did not fall away so much as fold, like pages closing. For an instant, Serin walked between one step and the next, between inhale and exhale, balanced on the thin edge of choice.

Their foot came down on something that was not the library floor.

Stone, perhaps. Or worn wood. The surface was solid under their boot.

Warmth washed over them. Voices swelled, still indistinct but closer now. Light—not the steady, sour light of study lamps, but something softer, alive with flicker and movement—pressed against their closed eyelids.

Serin did not open their eyes yet.

They rested a hand over the pocket where the folded page lay and, for the first time since they could remember, allowed themselves to stand in the not-knowing without flinching.

The fox’s presence brushed against their awareness like the lift of a tail around their ankles. An invitation. A promise.

Somewhere ahead, just beyond the reach of their senses, a room waited that countless stories had circled around but never quite named.

“Where lost paths meet,” Serin murmured.

The words slipped into the warm air and vanished.

When they opened their eyes, whatever lay beyond the frame belonged to another story—and another chapter.

Behind them, the tower of empty titles and forgotten questions was gone.

Ahead, in the unseen place the fox had led them to, the next lost path was already on its way.

Leave a comment