The war had ended three months ago.

That was what the posters said, anyway—peeling on brick walls, flapping on lamp posts, fluttering over the market like tired flags.

Teren ran his fingers over one of them, tracing the bold letters announcing Peace Declared as if they belonged to someone else’s story.

Behind him, the town breathed like a single vast creature. Laughter spilled from taverns and doorways, thin music threaded through the streets, and somewhere a drum beat slow and steady, calling people to celebration.

Teren’s heart answered with a different rhythm entirely: too fast, then too slow. Like a soldier out of step with the rest of the line.

He turned away from the poster and the noise. Away from the smell of roasting meat and spilled ale. Away from the steady, inevitable drum that reminded him of marching—of boots in mud, of shouted orders, of the hollow thump of bodies hitting the ground.

He shoved his hands into his coat pockets and walked until cobblestones gave way to packed earth, and the lamps thinned and then vanished.

He didn’t bother watching where he was going.

He had already been lost for a very long time.

The night at the edge of town was cold, and honest about it. No music, no laughter—just the rasp of dry grass, the creak of bare branches, the hiss of the river dragging itself over stones.

Teren followed the sound of water. It had always helped, once. Long before the uniform. Long before the weight in his chest.

He came to the old stone bridge, the one that arched over the Blackwater like a crooked spine. Moss grew between its blocks, and lichen shaved years from its surface.

He leaned against the rough stone, listening to the river and to the faint drumbeat of celebration carried faintly from behind him.

You should be there, he told himself. Your name’s on the wall. You came back. You’re one of the lucky ones.

His jaw clenched until his teeth ached.

“Lucky ones,” he whispered into the dark, the words bitter and small. “Tell that to Jorran.”

The name landed between him and the river like a stone.

Jorran’s laugh, Jorran’s hand on his shoulder, Jorran’s eyes turning surprised and then empty. Teren squeezed his eyes shut, but the images were etched on the inside of his eyelids. He could see them whether he wanted to or not.

He had pulled so many men back behind the line. He had dragged bodies, living and dead, through mud and smoke. That was what he had been good at: hauling, carrying, enduring.

Except that one time. The one that mattered.

He pressed the heels of his hands into his eyes until colors sparked against the darkness.

When he pulled his hands away, something else was there.

A light—a small one—hung in the air a short distance down the riverbank. Not high like a lantern on a pole. Low, close to the ground, as if someone had dropped a candle and forgotten it.

It flickered once, twice.

Then it moved.

Teren straightened, frowning. The light bobbed along the edge of the reeds, weaving between stones with a peculiar deliberate grace. It did not sway like something carried by a person. It glided, bright and steady, at the height of a child’s eyes.

“…Hello?” he called, because habit and training had taught him to announce himself, even when he wanted to vanish.

The light paused.

Then it turned toward him.

For a second, nothing else existed. Just the river’s hiss, the distant thud of celebratory drums, and that small, unwavering glow.

It brightened, just a little, as if answering.

Teren swallowed. He had seen strange things on the field—flares, tracer fire, the red bloom of artillery across the horizon—but none of them had ever made the air feel like this: sharp and thin, like a breath held too long.

“Right,” he muttered to himself. “Either I’m tired enough to be seeing lights… or someone actually needs help.”

The second thing hurt less than the first, so he chose it.

He slid down the slope from the bridge, boots skidding on damp earth. The light retreated a pace, just enough to stay out of reach, then waited like a patient guide.

“Fine,” Teren said under his breath. “Lead on, then.”

The light bobbed once, as though it understood.

And moved.

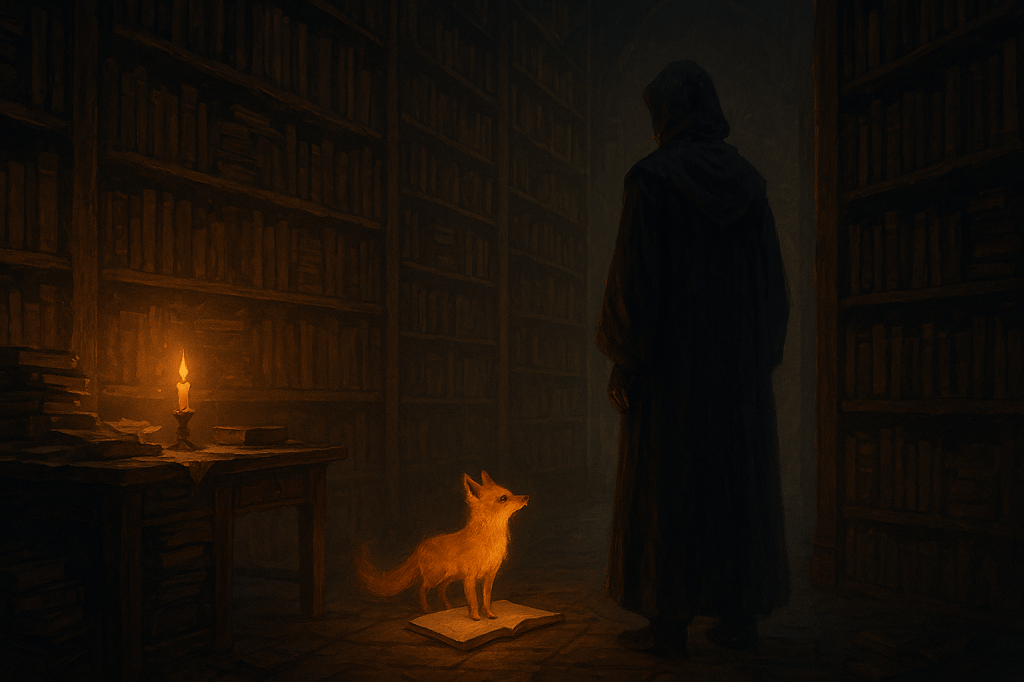

At first he thought it was a lantern, suspended by some trick of wire. But as he drew nearer, he saw the shape behind it.

A fox, no larger than any that skulked on the edge of fields—except for the way its fur caught the night, ember-bright along its back and cheeks, and the way its tail curved upward like a hook.

From the tip of that tail, a lantern hung. Not iron and glass, but a globe of soft golden flame, contained and impossible, suspended without chain or handle.

The creature watched him with eyes like polished amber. Its paws were silent on the earth. The lantern’s glow warmed his face, cutting the chill.

Teren stopped, breath caught halfway.

The fox tilted its head, studying him the way a scout studies a stranger at the edge of camp.

“I’m… I’m not drunk,” Teren said to it, mostly to convince himself. “And I’m not asleep.”

The fox blinked once, very slowly.

Then it turned and trotted along the riverbank, pausing only when it realized he wasn’t yet moving.

It looked back, lantern swaying gently. The light caught the deep lines etched into his face, the few silver threads starting at his temples, the tiredness pulling down his shoulders.

“This is ridiculous,” he muttered.

He followed.

The river narrowed and deepened to his right, a black ribbon in the night. To his left, the land rose in uneven humps and tangled bushes, dotted with the skeletal remains of summer’s trees.

The fox led him along a path he would have sworn wasn’t there whenever he’d walked this way by day. The ground underfoot was too smooth, the turns too natural, like worn stone in the threshold of an old doorway.

The lantern’s glow chased the worst of the shadows away, but Teren’s mind filled them in easily enough.

A figure slumped against a broken wall. The faint shape of a rifle. The echo of someone calling his name through smoke.

He dragged in a breath. The air here smelled of damp earth and fallen leaves, tinged with something else—oak smoke, maybe, and the ghost of spilled ale. It prickled at the back of his memory in a way that made him more uneasy than comforted.

“Where are you taking me?” he asked the fox, knowing he wouldn’t get an answer.

He was right. No voice answered. The fox just kept moving, tail-lantern swaying side to side in a calm, patient arc, the light laying down a narrow line for him to walk.

He realized after a while that he could no longer hear the town.

No drums. No laughter. No music.

Just the river, and the sound of his own breath, and the faint, soft click of the fox’s paws on stone.

They crested a low rise, and the world spilled open.

The clearing below them should not have been there.

Teren knew this stretch of land. Or thought he did. By day it was nothing more than scrub and a few gnarled trees, good for nothing but giving children a place to dare each other to climb.

Now, though—

Now the clearing held ghosts.

Not the translucent, whispering kind. These were made of memory and shape.

He saw a field churned to mud, pitted with craters. He saw torn banners whipping in a wind he could not feel. He saw the silhouettes of men and women in armor and in patched jackets, some kneeling, some standing, all watching something near the center of the space.

His own breath fogged in front of him. He could smell cordite, and blood, and wet wool. His stomach lurched.

“No,” he said. “No. We don’t come back here. I did my time.”

The fox’s lantern brightened, its glow widening until it brushed the edge of the vision below. The shapes sharpened. One of them moved in a way that hit Teren like a fist to the chest.

Wide shoulders. Lopsided gait. The way the man pushed his hair back with two fingers when he was trying to think.

Jorran.

Teren’s throat closed.

He stood frozen on the edge of the rise, watching his younger self—mud-streaked, eyes too wide—running toward the sound of gunfire, shouting Jorran’s name. Watching Jorran turn, relief breaking across his face.

Then the sharp, bitter crack of a shot. The way Jorran’s body jerked, then folded like someone had cut his strings.

Teren staggered back a step, fingers digging into his hair. It felt like the first time all over again. Weightless, stunned, unable to move fast enough as his memory-self dove for Jorran, hands pressing uselessly against the spreading red.

“I know how this ends,” he rasped.

The fox padded to his side, close enough that its fur brushed his trousers. The lantern swung forward, spilling warm light over the scene below, softening the edges of the worst of it.

The vision did not stop. It played on—his frantic hands, the medics arriving too late, the wild, pointless scream he never remembered making until someone told him later.

And then, as abruptly as a curtain falling, the sound dropped away.

The figures in the clearing froze. Jorran lay still on the ground, eyes half-open, expression caught midway between surprise and something else.

Teren realized he was breathing like he’d run a mile. His fingers hurt where nails dug into palms.

The fox stepped forward.

It did not speak. It did not explain.

It simply walked down the slope, light steady, until it reached the still form of Jorran in the frozen memory. It circled once, twice, then looked up at Teren, lantern casting long shadows across the ground.

Come, the gesture said. Not in words, but in the way its body angled, the way the light pooled in a path between them.

He didn’t want to.

He wanted to turn around, to walk back to the bridge, to pretend he had never seen any of this.

But he had been running from this exact moment for so long that his legs knew the path without him. They remembered the feel of mud and blood and the weight of his friend’s body.

He walked down into the clearing.

With every step, the ghosts grew less solid, like they were made of mist. The sounds did not come back. Only the soft chime of the lantern flame and the whisper of dry grass against his boots.

He reached Jorran’s side and dropped to his knees. His fingers hovered over the same place they had pressed once, long ago, trying to keep a heart beating that had already decided to stop.

The body beneath his hand was not real. His palm passed through fog and left it unruffled.

Teren’s chest hurt anyway.

“I tried,” he said, voice cracking. “I tried. I swear to you, I—”

He had said those words in his head so often that they had become a rhythm, a litany. They had never escaped his mouth before now.

“I should have been faster. I should’ve pulled you back sooner. I should’ve seen the sniper. I should have—”

The words tangled, choked. His shoulders shook.

The fox sat, folding its legs neatly beneath it. The lantern swayed gently, casting a circle of gold that pushed the worst shadows further back.

It watched him without judgment. Without pity. Just presence.

Somewhere in the silence, the drumbeat from town tried to intrude, but it sounded very far away.

After a long time, Teren scrubbed his face with the heel of his hand. His eyes felt raw. His ribs ached like he’d been in a fight.

“I don’t know how to do this part,” he admitted, not sure who he was talking to. The fox. Jorran. The river. Himself. “They told us how to march. How to shoot. How to stitch a man up and send him back out. Nobody ever told us how to come home.”

The fox’s lantern flared, then narrowed, as if breathing.

Jorran’s frozen face softened very slightly, the rigid lines easing. Perhaps it was a trick of the light. Perhaps not.

Teren reached out, hand shaking, and set his fingers lightly against the outline of his friend’s shoulder. The fog of the memory rippled under his touch.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered. “You shouldn’t be here in my head like this, stuck on the worst day. You deserved better.”

The words felt strange and heavy. As they left his mouth, the clearing seemed to exhale.

The ghosts in the distance blurred further, dissolving into shadows that looked more like trees than soldiers. The churned mud smoothed into earth, dotted with hardy grass. The smell of smoke thinned, replaced by damp leaves and distant rain.

Jorran’s outline shimmered.

“Rest,” Teren said. His voice was steadier now. “You did your part. You can… you can stand down, all right? I’ll carry the rest.”

Something loosened beneath his sternum, a knot he hadn’t known had a beginning.

The figure at his feet dissolved like breath on a mirror.

The clearing was just a clearing again.

Teren sank back on his heels, chest rising and falling. The fox came to his side, brushing lightly against his arm. The lantern’s glow settled, no longer flaring bright, just a steady, warm presence at the edge of his vision.

“Is this what you do?” he asked it quietly. “You drag people back through their nightmares and… sit with them until it hurts less?”

The fox’s ears flicked. It tilted its head as if considering his question, then turned away, tail swinging.

There was more to see.

The path out of the clearing led upward, through thinner trees. The fox took a different route than the one they had used to enter; Teren was almost sure of it. The land didn’t match any map in his mind.

They crested another hill, higher than the last. Here, the night sky opened fully above them, pierced by hard white stars. The river’s voice was faint now, distant but still loyal.

At the top of the hill stood a single stone.

It was not a grave marker, not exactly. No name had been carved into it. Moss clung to its base, and lichen painted pale sigils across its face. But there was a hollow in the earth before it, as if people had stood there before and wept, and their tears had worn a small depression into the ground.

The fox padded to the stone and sat, lantern shining against its weathered surface. It looked back at Teren.

He understood.

“I don’t even have his tags,” he said, throat thick again. “They sent them to his family. I don’t… I don’t have anything of his.”

Except memory, and guilt, and the way Jorran had made terrible jokes when everyone needed them most.

He reached into his coat pocket anyway, more out of habit than hope. His fingers brushed something metal.

He frowned, pulling it out.

It wasn’t Jorran’s tags, no. But it was a small disc of dull steel, stamped with Teren’s own number and name. A spare he’d kept without thinking, because that was what soldiers did.

He weighed it in his palm, the metal slick and cold with sweat.

“You want me to leave this?” he asked the fox.

The lantern’s glow brightened fractionally, catching the stamped letters, turning them momentarily gold.

He snorted softly. “You’re very free with other people’s belongings, you know that?”

Still, his feet carried him forward. He knelt before the stone. The earth there was softer than it should have been, welcoming.

He turned the disc over once, thumb brushing his own name.

Then he pressed it into the moss at the base of the stone.

“For Jorran,” he said. “And for everyone else who stayed, when I didn’t.”

It felt like confession. Like surrender. Like laying down a rifle he’d been carrying far too long.

The fox rose and circled the stone, tail lantern tracing a slow ring of light around it. For a heartbeat, Teren saw other shapes at the stone’s base: bits of ribbon, a button, a feather, a child’s carved toy horse. Offerings from other people, on other nights.

Then the image was gone, as if it had never been.

The wind shifted.

On that wind came music—not the rough tavern songs from town, but something lower and warmer. A fiddle, maybe, and the murmur of voices, and the clink of mugs on wood.

Teren turned, heart stuttering.

Far below the hill, where there should have been only trees and the far edge of town, a glow pulsed.

It was not the sharp yellow of gas lamps or the thin blue of electric light. It was a deep, steady amber, like the heart of a fire that had been burning for a very long time.

He could see the suggestion of a roofline, the faint outline of door and windows. Smoke rose from a chimney that faded into the stars. For a moment, he swore he saw a sign swinging above the doorway, catching the light in a way that suggested painted metal and old wood.

He leaned forward, squinting.

The details refused to resolve. Every time he thought he caught hold of them, they slid out of focus, like a half-remembered dream.

He could hear laughter, though. Not the raucous, brittle kind. The rich, quiet sort people make when they are finally safe.

His chest ached with a surprising, almost painful desire to be inside that light. To feel warmth at his back and a solid mug in his hands, and to sit with others who understood what it cost to keep standing.

He took a step down the hill.

The fox stepped gracefully in front of him, blocking the path.

It didn’t growl. Didn’t bare its teeth.

It simply looked up at him, lantern reflecting in its eyes, and shook its head—just once.

Not yet.

Teren swallowed.

“Not for me, then?” he asked, voice rough.

The fox blinked slowly. The distant glow pulsed, just for a heartbeat, as if in answer. The music curled around his ears, a promise more than a presence.

Then, like a candle snuffed under a cupped hand, it vanished.

The hillside below was only dark again. Trees and shadows. Ordinary night.

Teren stood very still.

The fox touched its nose lightly to his knuckles. The lantern’s warmth soaked into his skin, sinking up his arm, settling somewhere beneath his ribs.

The place that had been all stone and ache was… not empty now. But different. Like a room where the furniture had been rearranged, and you weren’t entirely sure where everything stood, only that there was breathing space again.

“Right,” he said after a moment, scrubbing at his face. “Right. I hear you.”

He looked down at the stone one last time, at the disc half-hidden in the moss.

“I’ll go home,” he promised Jorran, and the stone, and the quiet fox, and himself. “Properly, this time.”

The fox’s lantern dipped in a small, solemn bow.

The path back to the bridge felt shorter.

They walked in silence. The night seemed to have softened—still cold, still wide, but less like a set of teeth waiting to close and more like a cloak settled around his shoulders.

By the time the murmur of the town reached his ears again, the drumbeat no longer sounded like marching. It sounded like dancing. Like hearts finding a common rhythm, instead of grinding against each other.

They reached the slope below the bridge. The stones were slick with river mist. Teren climbed up first, then turned back.

The fox stood at the bottom, golden lantern reflected in the dark water.

“Will I remember this?” Teren asked.

He already knew the answer. He had heard stories, growing up—half-remembered tales told in winter about lights that led the lost through snowstorms and fog, about a fox with a lantern on its tail that guided people where they needed to go.

Sometimes people said they dreamed it all later. Sometimes they swore they had simply walked, and walked, and walked, and found themselves exactly where they needed to be, with no memory of the in-between.

The fox’s lantern dimmed slightly, its edges softening. The air around it shimmered.

“Yeah,” he said. “All right. Maybe that’s for the best.”

He hesitated, then added, “Thank you. For… sitting with me. For not making me do it alone.”

The fox’s ears flicked. For an instant, the lantern brightened again, so bright it threw his shadow long across the bridge stones.

Then the glow collapsed inward, like fire curling around itself.

When his eyes cleared, the fox was gone.

Only the ordinary night remained. The river. The bridge. The faint call of someone laughing, carried from town.

Teren looked at his hand.

His knuckles were warm, as if a small coal had been pressed there and then removed. When he closed his fist, the warmth settled deeper, a quiet ember inside his chest.

He turned toward the town.

The posters would still be on the walls. His name would still be on the plaque. The taverns would still be loud. People would clap him on the back and tell him he was a hero, and some part of him would still flinch.

But for the first time since he’d stepped off the transport, he felt like the road ahead led somewhere other than back to that moment in the mud.

He walked toward the lights.

Behind him, unnoticed, a tiny glimmer flickered once at the edge of the trees—like a fox’s lantern, watching, waiting, ready for the next broken heart that needed help finding its way home.