By the time the bells stopped ringing, the prophet had already stopped listening.

Once, the sound of them meant something—a pattern in the echoes, a rhythm in the sway of the ropes, little threads he could follow into glimpses of tomorrow. People used to climb the hill just to ask him what the bells meant.

Now they just rang because it was evening and that was what bells did.

He sat alone on the temple steps, cloak wrapped tight against the cold, staring at the worn grooves carved by years of feet and weather. A crooked staff lay across his lap. The top of it had once held a crystal that shimmered in starlight. Now it was bare wood, splintered where the stone had cracked and fallen away.

“Nothing,” he murmured, rubbing his thumb along the break. “Empty sky. Empty dreams. Empty head.”

The lamps along the path below flickered on, one by one, as the acolytes moved through the courtyard. He could hear them whispering, careful-soft, the way people do when they’re afraid their words might shatter something fragile.

He didn’t blame them. He’d shattered it himself.

The last vision he’d spoken aloud had been wrong.

He had stood here, on this same step, and told the gathered crowd that the river would rise and swallow three streets if they did not leave their homes. They had packed their lives into carts and baskets and crates, herded children and animals up the hill, and waited in the temple, watching the river below.

The waters stayed where they were supposed to stay.

For three days, the village camped in the temple halls, huddled between incense smoke and carved stone, waiting for the disaster that never came.

When they finally went home, they did not look up at the hill.

And the bells that had once sounded like prophecy just sounded like bronze.

Now, when he closed his eyes to listen, the silence inside his own skull felt louder than any warning he’d ever spoken.

“I can’t see,” he whispered, though there was no one there to hear. “Not the old way. Not any way.”

He might have gone on sitting there until the cold crept all the way into his bones—if the light at the edge of the courtyard had behaved the way light usually does.

Instead of brightening steadily with the lamps, one spot at the base of the hill flared, dimmed, and flared again, like someone cupping a flame and then opening their hand.

He frowned and straightened, squinting.

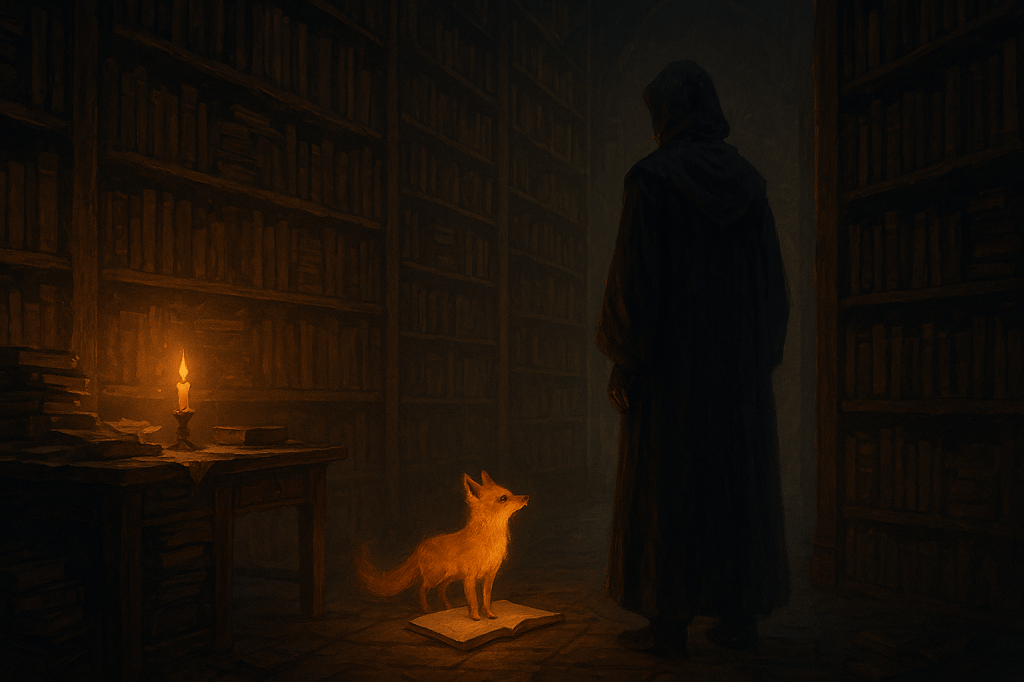

There, just beyond the last carved stone lantern, something small and fox-shaped stepped into view.

At first he thought he was looking at one of the temple cats catching the fireglow, but this light was wrong for that. It didn’t reflect off fur; it seemed to spill from it.

The creature’s coat was ember-brown, tipped with brighter orange where the fading daylight caught it. From the end of its tail hung a small lantern, no bigger than a teacup, casting out a warm, golden glow that made the nearby shadows lean away.

The prophet blinked hard and then blinked again.

The fox remained.

“You’re late,” he told the air, because old habits die slower than faith. “Visions usually come before I give up.”

The fox tilted its head. The little lantern on its tail swung, sending rings of soft light across the stones.

It didn’t speak. There was no booming voice, no echo of some distant god curling around the corners of his thoughts. There was only the seeable, solid fact of a small fox with a light tied to its tail, watching him with eyes the same color as its lantern.

“You’re real, then,” he said slowly. “Or I’ve gone properly mad.”

The fox padded closer. Its paws made no sound on the worn stone. At the foot of the steps, it paused, looked at him, then turned away and started down the path that led away from the temple, toward the terraced fields and the ravine beyond.

The lantern’s light tugged the darkness along behind it like a long black cloak being peeled back.

The prophet hesitated.

He had ignored one false vision and lived with the shame of being wrong. Now something that looked like it had walked out of a story stood in front of him, offering nothing—no words, no promises—just a path lit a few steps at a time.

He could stay, with his broken staff and his broken certainty.

Or he could stand up.

His knees complained when he pushed himself to his feet. The bells finally stopped ringing behind him, leaving the world strangely bare. He took up his staff, feeling the splintered top bite his palm, and followed.

“Fine,” he muttered as he limped down the steps. “If you’re a dream, at least you’re a new one.”

The temple lamps grew fainter behind them. Ahead, the lantern-tail painted low walls and dry grass in gold and amber. The fox never rushed, never slowed, moving with that effortless, patient trot that wild things have when they know exactly where they’re going.

“Do you know where you’re going?” the prophet asked after a while, half to himself. “Because I don’t.”

The fox’s ears flicked but it gave no other answer.

They left the main road almost immediately, cutting across a fallow field where the stubble scratched at the prophet’s boots. He stumbled once when his foot caught on an old root hidden in the dark, and his temper flared up sharp and quick.

“This is ridiculous,” he snapped. “I’m too old to be chasing lights. I’m not some wide-eyed apprentice waiting for my first omen. I’m a—”

The word prophet caught in his throat like a stone.

The fox stopped. The lantern’s glow reached only to the tips of the prophet’s boots. Beyond that, the night swallowed the world whole. Crickets chirped. Somewhere far off, a dog barked twice and then thought better of it.

Slowly, the fox turned, looking back at him.

Its eyes were not accusing. They weren’t anything that simple. They just were, with the steady, quiet attention of something that has watched storms rise and fall and knows that temper is smaller than lightning.

The prophet let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

“I don’t know what I am,” he admitted.

The lantern brightened. Just a little. Enough to reach his hands, to paint his broken staff in gentle gold.

He swallowed.

“…All right,” he said more softly. “Lead on.”

The fox turned and trotted down into the ravine.

The path grew steeper and less certain. Dirt turned to loose stone. Shrubs scratched at his cloak. Once or twice he heard the rattle of pebbles sliding into unseen depths.

“Wonderful,” he muttered. “Follow a strange fox into a dark gully. Very wise. This is exactly the sort of decision people come to the temple to avoid making.”

But he kept going.

The lantern-light never stretched more than a few strides ahead. He could not see where the path ended, only where his next step landed. All the wild maps his mind used to draw—branching futures, weight of choices, the way one word could spool out into a dozen consequences—refused to appear.

Step. Staff. Breath.

The world shrank to that.

At the base of the ravine, a thin stream whispered over stones. The fox leapt lightly across. The prophet followed more slowly, boots slipping on moss-slick rock. His foot plunged into the cold water and he hissed, half from the shock and half from the old ache in his bones.

The fox paused on the opposite bank, looking back as if weighing whether he would turn around.

He didn’t. Not yet.

They climbed again on the far side, up through a tangle of roots and old, broken shrines. The statues here were different from the ones at the temple above—rougher, older, worn faceless by rain and time. People had stopped coming down this way generations ago, if they had ever come at all.

At one crumbling altar, covered in moss and half-choked by a fallen tree, the fox halted so abruptly that the prophet nearly walked into it.

“What?” he asked, catching himself. “What is this place?”

The fox stepped aside. The lantern’s light fell directly on the cracked stone bowl at the altar’s center.

Inside it lay fragments of glass and crystal—sharp, glittering shards that caught the lantern-glow and scattered it in a dozen directions. Some pieces were clear, some smoky, some faintly colored, like slices of frozen dawn.

The prophet stared.

“I know you,” he whispered, reaching out.

His broken staff trembled in his hand.

Once, long ago, when he was young and the world was full of possibilities instead of questions, this had been his altar. This ravine had been his secret place, where he had first learned to quiet his thoughts enough to notice the way the world hummed underneath ordinary sound.

He’d shattered the crystal himself when his first terrible vision came true, convinced that no one should have to see what he’d seen. He’d thought breaking the tool would break the sight.

He’d been wrong. The visions had come anyway. The crystal had been forgotten.

Until his last prophecy failed.

Until the river did not rise and the people stopped asking and the silence in his head became more frightening than any disaster he could imagine.

“I thought I was beyond this,” he said, voice rough. “Beyond hiding in ravines and talking to strangers and asking the dark what it wants from me.”

The fox hopped up onto the altar. Its paws did not disturb the glass fragments. The lantern at its tail swayed over the shards, and each one flashed with a different small reflection.

Here, a sliver of the sky turning bruised-purple over a field. There, the shine of water on stone. In another piece, so small he had to lean close to see it, a slice of village street lit by lanterns… people laughing, holding cups, their faces indistinct but warm.

He reached toward that shard, then hesitated.

His hand shook.

“I was wrong,” he whispered. “Once. I trusted what I saw, and it hurt people. What if I pick up the wrong piece again? What if I only ever see the pieces that scare me?”

The fox’s gaze didn’t flinch, didn’t soften.

It simply waited.

The prophet swallowed. The night pressed close around them, full of its own quiet breathing. Somewhere above, the temple bells hung heavy and still, their ringing a memory now.

He thought of all the years he had tried to drag certainty out of a sky that had never promised him any. Of the way people’s shoulders loosened when he told them, “It will be all right,” even when he hadn’t been sure. Of the terrible relief in their eyes when he warned them of something they avoided.

He thought of the river that had not risen, and the way he had sat with that failure like a stone in his chest, as if one wrong glimpse meant he had no right to look at all.

“Maybe,” he said slowly, “maybe they were wrong to think I could see everything. And maybe I was wrong to let them.”

His fingers closed around the small shard with the laughing, lantern-lit street.

It was cool against his skin. For a heartbeat, he felt something—not a voice, not a command. Just a sense of warmth, of a room somewhere that did not exist yet, where lost travelers set down their burdens and thawed their hands beside a fire that never quite went out.

He did not know where it was. He did not know when.

He only knew that, someday, it would matter.

The knowledge did not slam through him like a thunderbolt. It settled in his chest like an ember, fragile but real.

He slipped the shard into a pouch at his belt.

“Fine,” he said to the fox. “I’ll try again. But differently this time.”

The lantern brightened. The fox hopped lightly off the altar and started up the path out of the ravine, tail swaying, light bobbing.

The prophet followed.

By the time they climbed back to level ground, his legs ached and his breath came short. The village lay below them like a scattering of stars, small lanterns glowing in windows and along streets. Further off, the dark line of the river curled like a sleeping serpent.

He had expected to feel the old pull—the urge to scan the sky, to sift the wind, to search for cracks in the pattern where disaster might creep in.

Instead, all he felt was… tired. And, quietly beneath the tired, a thin thread of something like relief.

The future did not rise up in his mind in blazing clarity. No sudden storms bloomed in his thoughts. No hidden wars marched across the back of his eyes.

There was just the next step.

And the next.

And the little circle of fox-light on the grass.

They walked along the ridge until the path narrowed to a cliff edge. Below, the ravine they’d climbed out of dropped away into darkness. Ahead, there was no more ground, just air and night.

The fox stopped.

The lantern on its tail swung lazily over the drop. The prophet could see nothing beyond that thin halo of light. The world might as well have ended there.

“I can’t walk where there isn’t a path,” he said, the old panic curling quick in his stomach. “Show me where it goes. Just this once. Just so I know it is there.”

The fox looked back at him.

Then, without a sound, it stepped off the edge.

The prophet gasped and lurched forward, hand outstretched, as if he could catch the little creature by its tail. But the fox did not fall. Its paws met something unseen. The lantern light shivered… and held.

Where there had been only darkness a moment before, its glow now revealed a narrow ledge of stone, hugging the cliff face. A path, thin and precarious, but a path all the same.

“Oh,” he breathed.

The fox took another step, and another, light bobbing. Each time, just a little more of the ledge appeared, far enough ahead to place a foot, never far enough to see where it ended.

The night swallowed everything beyond that soft, golden circle.

The prophet stood at the edge, heart pounding.

“This is what it’s like for them,” he realized. “For everyone who ever asked me what was coming. They don’t get to see it the way I thought I did. They only ever get this much. A few steps. A small light.”

He looked down at his hands, at the old scars from ink and candle burns and broken glass. At the faint shimmer of the shard in his pouch.

Maybe… the question had never been, What is the future?

Maybe it had always been, How do we walk when we can’t see it?

The fox paused, halfway along the invisible ledge, and sat down. It did not look impatient. It simply waited, tail curled around its feet, lantern swinging in the open air.

The prophet laughed then, quietly and a little shakily.

“All right,” he said. “I understand.”

He stepped out over the edge.

For a heartbeat, his stomach dropped. Then his boot met stone.

Solid. Narrow. Real.

The world beyond the light remained utterly black, a velvet nothing. If he looked too far ahead, his balance wavered. So he stopped trying. He put his attention where the light was—the next step, and the next, and the feel of the ledge under his feet.

He could not see where the path led. He walked anyway.

His fear didn’t vanish. It moved. It settled into his chest beside that ember of warmth, both of them glimmering quietly together.

Halfway across, the wind shifted. A smell drifted past him—smoke and cinnamon and something sweet, like honey warming over a hearth. For a moment, carried on the breeze from nowhere at all, he heard the low murmur of voices and the soft clink of cups.

A room, he thought. Somewhere. Somewhen. Lit by lanterns that never quite went out.

Then the wind changed again and it was gone.

He stepped onto solid ground.

When he turned, the ledge was disappearing behind him, swallowed piece by piece by the dark. The fox hopped lightly back onto the grassy ridge at his side, as if it had simply been crossing a street.

They stood together for a while, looking back at the invisible path.

“I used to think I was meant to see everything,” he said at last. “Every danger. Every blessing. Every twist in the road. Maybe my vision breaking wasn’t punishment. Maybe it was… mercy.”

He smiled, small and slow.

“Maybe this is enough. A light for the next few steps. A reminder that there is still a way forward, even when I can’t see the whole of it.”

The fox bumped its head softly against his leg. The lantern brushed his cloak, leaving a faint warmth behind like a hand pressed to his side.

“Thank you,” he said.

He did not ask where it had come from. He did not ask where it was going next. For the first time in a long time, he did not ask what would happen tomorrow.

He knew what he would do when he walked back down the hill.

He would stand on the temple steps—not as a man who claimed to know every turn of fate, but as someone who had walked a narrow path with only a small light. He would tell the people the truth:

That no one could see everything.

That fear did not vanish just because you named it.

That sometimes, the bravest thing you could do was take the next step without knowing where the path ended.

And that somewhere, in some not-yet-built place between roads and rivers and worlds, there was a door that would one day open onto warmth and music and rest.

He did not know how he knew that.

He only knew that when he slipped his fingers into the pouch at his belt, the little shard of glass there pulsed once against his skin, like a heartbeat.

When he looked down again, the fox was already moving.

Back along the ridge.

Back past the silent bells.

Back toward whatever corner of the world held the next person lost enough to follow a small, golden light into the dark.

The prophet watched until the glow of its lantern melted into the other lights of the night, indistinguishable from stars and windows and dreams.

Then he turned toward the temple and began to walk, step by careful step, trusting the path beneath his feet—even when he could see only a little way ahead.