(The Grieving Parent)

The hallway light had been burned out for months.

Mara liked it that way. Darkness made it easier to walk past the door without looking at the little brass plaque with the chipped paint and the sticker in one corner that read Super Explorer.

The door stayed closed. The door stayed closed because if she opened it, the room would be different. It would be full of dust instead of laughter, stale air instead of the scent of crayons and sticky fruit snacks. As long as it was closed, the picture in her mind stayed the same: a small bed with space-ship sheets, a stuffed rabbit slumped on the pillow, a crooked poster of planets on the wall.

She carried her mug from the kitchen—lukewarm tea she’d forgotten to drink—past the door like she did every night. One, two, three, four… She counted the steps between her bedroom and the nursery without meaning to. Her hands knew this path even when her mind didn’t want to.

Halfway past, she stopped.

There was light under the door.

Not the thin, sickly orange from the streetlamp outside, sneaking in through old curtains. This was warm and soft and golden, like candlelight trapped in honey, breathing with a slow, gentle pulse.

Mara’s first thought was short circuit. The wiring in the house was old. Maybe something had finally caught—a lamp left plugged in, a nightlight she’d forgotten to unplug that afternoon. Her chest tightened. She couldn’t bear the thought of that room burning, of losing the last shape of it.

She set her mug on the floor with a clink she barely heard and pressed her palm to the door.

Warm. But not hot.

The knob was cool, smooth under her fingers. She turned it, expecting the creak she’d heard a thousand times.

The door opened without a sound.

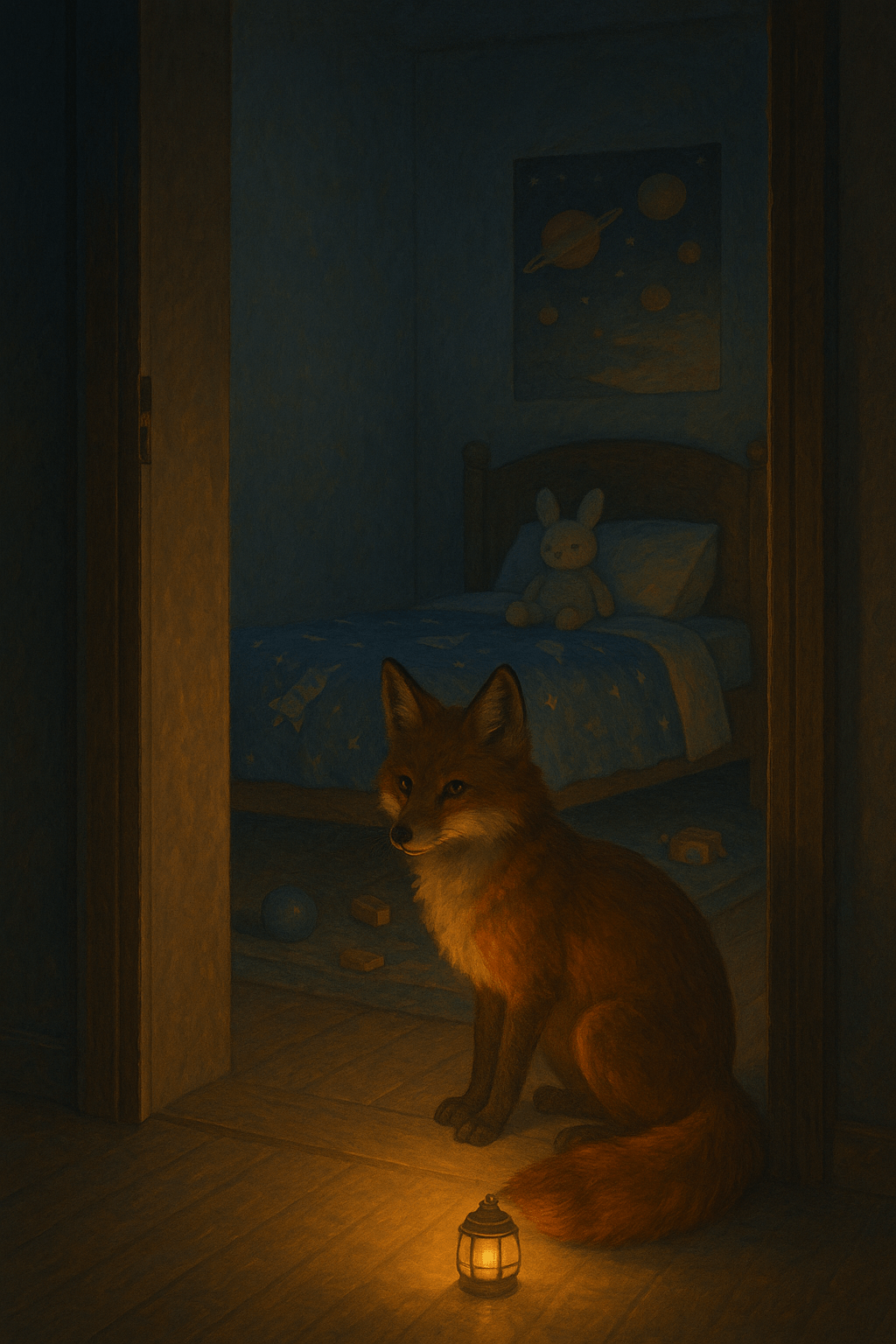

The nursery was exactly as she’d left it the day she’d shut it for the last time.

Tiny bed. Space-ship sheets. Stuffed rabbit on the pillow, one ear folded over. Crayon drawing taped to the wall, corners curling. The mobile above the bed hung still, tiny wooden moons and stars frozen mid-orbit.

And in the middle of the worn rug, curled like a sleeping ember, was a fox.

Its fur was the color of late autumn leaves kissed by fire—russet and gold and a deeper, coal-dark red along the spine. Its ears were tipped in soot-black, and its paws seemed dusted with ash. Its eyes, half-lidded, reflected the light that swung gently from the lantern hanging from its tail.

That lantern was the source of the glow. It was small and round, made of panes of glass that might once have been clear, now stained in warm amber. A simple metal frame held it together, worn and dented as if it had crossed a great many roads. Inside, an unseen flame smoldered: not bright enough to hurt the eyes, but so warm that the shadows on the walls shivered and softened.

Mara stood in the doorway, fingers gripping the frame so hard her knuckles ached.

“…What,” she whispered, “are you?”

The fox lifted its head. The lantern on its tail swung, casting sleepy arcs of gold across the ceiling. For a heartbeat, the mobile above the bed seemed to turn, the carved moons catching the light as if moved by some invisible breeze.

The fox didn’t speak. It simply watched her, ears pricked forward, eyes calm and deep and impossibly old.

“I’m dreaming,” Mara muttered. Her voice sounded wrong in the small room—too big, too sharp. She hadn’t spoken in here since the funeral. “This is… this is some kind of grief hallucination. I’ve finally snapped.”

The fox blinked slowly, then unfolded itself from the rug in one sinuous motion. Its paws made no sound on the floor. Tiny paw pads pressed little crescents into the dust, and where it stepped, the dust seemed to retreat, leaving faint, clean prints that faded as the lantern light passed.

It padded across the room toward the small dresser where a row of toys sat like patient guardians. Little plastic astronauts. A wooden car. A stuffed bear with one eye missing. A stack of picture books.

The fox paused by a faded blue ball with a chipped silver star painted on the side.

Mara’s breath caught. “Niko’s ball,” she said, before she could stop herself. The name slid out and hung in the air, heavy and bright, like a star that had forgotten how to fall.

The lantern brightened.

For a moment, the light flared around the ball, wrapping it in a soft halo. The golden glow thickened, deepened, until shadows seemed to peel away from the corners of the room, drawn toward that one point.

Mara saw, not with her eyes but with the aching space behind her ribs, a flash of motion: small hands flinging the ball too hard down the hallway, giggles spilling after it. Niko’s socked feet skidding on hardwood. “Again, Mama! Again!”

She shut her eyes. The memory pressed at her, sharp and tender.

When she opened them, the fox had the ball in its mouth, the lantern on its tail swaying gently. It turned toward her, head tilted, as if asking a question.

“I can’t,” she whispered. “I can’t do this. I can’t—”

The fox brushed past her in the doorway, fur whispering against her leg. Warmth radiated from it, not hot like fever, but like holding your hands over a hearth on a winter night. The lantern grazed the frame as it passed, and for a heartbeat, Mara thought she saw soot-dark paw prints dancing along the wood, circling the door like a small, patient orbit.

The fox padded into the hallway. It paused, looking back over its shoulder, lantern swinging gently.

An invitation.

Mara found herself following before she decided to move.

Out of the nursery. Down the hall with its familiar creaks and small scars in the paint. Past the bathroom where she’d sat on the floor and sobbed into a towel so no one would hear. Past the coat closet with the bright yellow rain jacket still hanging inside, too small now for anyone.

The house was strange in the lantern light. The familiar lines of furniture blurred at the edges. The framed photos on the walls seemed deeper somehow, the faces inside them more alive. Mara caught glimpses as she passed—Niko at three with ice cream on his chin, Niko at four holding up a lopsided snowman—but the fox never stopped, and neither did she.

It led her to the front door.

“You want to go outside?” she asked, voice brittle. “It’s… it’s the middle of the night.”

The fox sat back on its haunches, ball at its feet, lantern swaying softly. It looked at the door, then at Mara.

Her hand shook as she worked the deadbolt. The outside world felt too big, too loud, too indifferent these days. She went out only when she had to: work, groceries, appointments where strangers said words like processing and stages and acceptance.

The latch clicked. Cold air slipped in around the edges, smelling of damp pavement and distant woodsmoke.

The fox slipped through the opening as soon as she cracked it, tail lantern swinging like a private star. Mara hesitated on the threshold.

The porch steps fell away into darkness. Streetlights flickered far off, their usual harsh glare dimmed and softened by the fox’s glow. The houses opposite looked… quieter, somehow, their edges blurred like watercolor. The world felt both more solid and less real, like stepping into a photograph you’d looked at too often.

Mara drew a ragged breath and stepped outside.

The fox trotted down the walk, paws leaving faint smudges of light on the concrete that faded with each step. The night seemed to bend around it, sounds muffled. No hum of distant cars. No sirens. Just the soft brush of fox fur, the faint clink of glass as the lantern swayed, the sound of her own breathing.

They turned down the street.

The way the lantern lit the sidewalk was strange. It didn’t simply push the darkness away; it carved a small, moving bubble of warmth in which each crack in the concrete, each fallen leaf, each weed pushing through the edges was illuminated with almost reverent care.

They walked past the closed corner store. Past the bus stop where she used to wait with Niko, his small hand tucked in hers, his backpack always a little too big. A gust of wind stirred the advertisement poster there, and for a second she thought she saw a different picture entirely: a wooden sign with a fox etched into it, a lantern hanging beneath, swaying in a wind that didn’t touch this street.

She blinked, and the image was gone. Just a smiling actor holding a paper cup of coffee remained.

The fox looked back once, as if checking she’d seen it.

“Where are we going?” Mara murmured, even though she knew it wouldn’t answer.

The fox padded on.

They reached the park.

The gate—old, chipped green metal—stood slightly ajar. The fox slipped through the gap without slowing. Mara swung the gate wider with a dull squeal of hinges, flinching at the sound cutting through the softened night.

Inside, the park was empty. The swing set stood in a row like waiting question marks. The slide gleamed faintly. The sandbox was a pale smudge in the earth, ringed by tiny abandoned footprints that belonged to no one now.

This was the last place she’d been with Niko before—

She drew in a breath so fast it hurt and clutched at the ache in her chest.

The fox walked to the middle of the playground and set the blue ball down. The lantern brightened, stretching shadows long and thin across the grass. The slide’s metal seemed to catch the light like a blade; the chains of the swings glowed softly, each link outlined in gold.

For a moment, the park wasn’t empty.

In the lantern’s radiance, Mara saw quick hands grabbing at the swing chains, saw short legs pumping, heard a laugh like a bell. She saw herself from the outside, pushing, saying “Higher? You’re brave, little comet,” and Niko’s answering shout: “I’m not little!”

But there was no body in the swing now. Just wind gently rocking the chains, squeaking quietly.

The lantern dimmed again, returning the park to hollow stillness.

Mara sank onto the nearest bench. The wood was cold under her, damp from earlier rain. Her hands trembled in her lap. Tears blurred the lantern’s glow into a soft smear of gold.

“It’s not fair,” she whispered. “He should still be here. He should— he should be running. He should be…” Her throat closed.

The fox stepped closer.

Without ceremony, it hopped up onto the bench beside her, light lantern tail resting along the back. The warmth from its body seeped into her side, into the stiff, locked muscles between her ribs. It pressed its head gently against her arm, as if nudging her to look up.

She did.

Beyond the playground, past the last row of trees, there was something that hadn’t been there before.

At first, she thought it was mist. A silver ribbon hanging in the air, just above the ground. Then the lantern light reached it, and the shape resolved: stepping stones hovering over a water that reflected no stars, stretching out into a blank darkness that didn’t feel empty, exactly. Just… beyond.

The nearest stone was only a few paces away.

Mara’s pulse thundered in her ears. “Is that…?”

She couldn’t finish the thought. The words felt dangerous, as if saying them would drag her forward or shatter the fragile, impossible moment.

The fox slid off the bench and padded to the edge of the water-that-was-not-water. The lantern brightened, casting rings of light across the surface. It rippled not like a lake, but like memory—scenes disturbed by the tiniest disturbance.

Mara saw baby fingers curling around her thumb. The first time Niko had pointed at the moon. A sticky kiss on her cheek, a weight on her shoulder as he fell asleep against her.

She stood up slowly.

Her legs felt like they belonged to someone else. She took one step. Then another. Each footfall echoed more loudly than it should have, like footsteps in a church.

The fox waited by the first stone.

“I can’t follow him,” Mara whispered, realization cutting through the fog in her mind like a cold wind. “I know. I know I can’t. It’s not my time.”

The fox’s lantern flickered, acknowledging. It looked at the stone, then at her, ears tilted forward, patient.

She understood, then, what it was asking.

Not to follow. Just to come close enough to say what she’d never let herself say. To admit what she kept folded like a secret in the dark spaces between her heartbeat.

Her whole body shook. She wrapped her arms around herself, fingertips digging into her sleeves.

“I don’t know how,” she said.

The fox took one small step, placing its forepaws on the first stone.

The lantern flared once, bright and steady. The warmth rushed over her like a breath from a door just opened onto a room that had been closed too long.

Mara stepped forward.

Her foot touched the stone. It was neither wet nor dry, neither warm nor cold. It simply was, solid and real under her weight. The water beside it—if it was water—stilled, reflecting only the lantern’s glow and something else, far off: the blurred suggestion of a small hand waving from beyond the last visible stone.

She didn’t try to see more. She was afraid that if she did, she would never step back.

The fox leaned against her leg, anchoring her here, in this one step of the bridge between worlds.

“Niko,” she said.

His name rang out into the not-water, into the dark, into the hollowed-out space inside her. She hadn’t said it out loud in weeks. Not alone. Not without someone there to pat her hand and tell her she was being “so strong.”

“I’m so sorry,” she choked. “I’m so sorry I couldn’t— I didn’t— I should have…” The words tumbled over each other and fell away, useless.

The lantern’s light flickered in time with her breath. With each shuddering inhale, it swelled. With each stuttering exhale, it dimmed, then steadied again, as if matching her, refusing to let her disappear into the dark.

“I love you,” she forced out. The words came out ragged, broken. “I love you, and you’re not here and it hurts and I don’t know who I am without you, and I feel so guilty every time I laugh because it feels like leaving you behind, and I don’t know how to carry all this and still go on, but I—”

Her voice cracked. Tears blurred everything into gold and black.

“And I will,” she whispered. “I will go on. I’ll keep going. I’ll carry you with me. Not like this—” She gestured vaguely toward the dark park, the locked hallway, the closed door waiting at home. “Not frozen. Not stuck. I’ll try to live. For both of us. Somehow.”

The words didn’t fix anything.

They didn’t bring him back. They didn’t erase the silence that would always echo where his laugh had been.

But they did something small and important.

The lantern’s flame surged, shooting a thin, bright beam over the water. It struck the farthest visible stone and shattered into a thousand tiny embers that drifted slowly back toward her, falling not into her hands, but into her chest, sinking without heat or pain.

The weight inside her shifted.

Grief was still there, but the sharpest edge dulled, wrapped in something gentler. Not acceptance—she wasn’t ready for that word—but an admission that the love didn’t have to be a locked door, that it could be a lantern she carried forward, light leaking through the cracks.

The fox stepped back off the stone, leaving her there.

It looked up at her, eyes reflecting not only the lantern’s glow, but the faint light that had kindled behind her own.

Then, with a small, decisive shake of its fur, it turned and padded back toward the playground.

Mara wobbled as she stepped off the stone. The world felt too heavy and too light all at once.

When she glanced back, the water and stones were gone.

Only the field stretched behind the playground, damp and dark and ordinary. The night noises crept back in: a distant car, a dog barking somewhere, the whisper of leaves.

The fox waited by the gate, tail lantern dimmed to a quiet ember.

Mara followed it home.

The streets were the same, and not. The bus stop was just a bus stop again, though for a moment she thought she heard the faint clatter of mugs and the low murmur of voices, as if there were a warm room just out of sight somewhere beyond the glass—somewhere travelers rested before moving on. If such a place existed, she thought, the fox would know the way.

Back at the house, she paused on the front step.

The porch light she’d never replaced was still dead. Only the lantern lit the chipped paint, the worn welcome mat, the hairline cracks in the stairs. The fox paused by the threshold, looking back at her.

“I don’t want to close his door anymore,” she heard herself say. “Not like a tomb. And I don’t want to keep it frozen, either.”

Her hand moved to the doorknob.

Inside, the hallway felt different. Not because anything had changed, but because she had. The darkness was the same, but it no longer felt like a wall; it felt like a canvas waiting for the smallest mark.

The fox padded straight to the nursery and sat before the open door.

For the first time since that awful day, Mara stepped into the room with the lights off and didn’t flinch.

She went to the bed and picked up the stuffed rabbit, its fur worn thin in patches, one eye slightly loose in its socket. She hugged it to her chest and inhaled dust and faint, lingering traces of laundry soap.

“I’ll keep this,” she said softly.

The fox’s lantern brightened in approval.

She moved slowly, carefully. She opened the blinds a little, letting the first thin threads of dawn sneak in. She cracked the window an inch to let the stale air breathe. She righted the picture on the wall that had been hung crooked for months.

She didn’t pack anything yet. That would come later. Not today, and maybe not tomorrow. But the room was not sealed anymore. Not a reliquary. Not a wound she refused to look at. Just a room, filled with memories and quiet and light.

By the time the sky outside had paled to soft grey, the fox was curled again on the rug. Its eyes were closed, but the lantern still glowed faintly, a drowsy coal.

Mara knelt beside it.

She didn’t try to pet it. Somehow, that felt like the wrong kind of touch, too casual for whatever it was. Instead, she bowed her head slightly, as if standing at the threshold of a sacred place.

“Thank you,” she whispered, voice hoarse but steadier. “For… walking me there. And back.”

The fox’s ears twitched. The lantern brightened one last time, flaring gently, filling the room with a light that smelled faintly of woodsmoke, autumn leaves, and something else she couldn’t name—a hint of distant music, of clinking cups, of laughter in a place between storms.

When the brightness faded, the rug was empty.

No fox. No lantern. No soot-prints on the floor.

Just the early morning light creeping across the space-ship sheets, touching the edges of a room that had been caught in the same moment for too long.

Mara stood in the doorway, hand on the frame.

For months, she had closed this door to keep the pain contained. Now, she left it open. She walked down the hall to her own room, found a small nightlight in the drawer beside her bed—a cheap plastic fox she’d bought on impulse years ago and never used—and plugged it into the socket by the nursery.

The little fox glowed with a gentle amber light.

It wasn’t the same as the lantern’s glow. But it was enough to keep the hallway from being completely dark.

On her way back to bed, she thought she saw, just for an instant, the tip of an ember-bright tail disappearing around the corner, as if some small, weary traveler were stepping through a door that opened onto a road no map could show.

Mara smiled, the expression strange and stiff on her face, as if unused muscles were trying a familiar shape again.

“Wherever you’re going,” she murmured into the quiet house, “may your lantern never go out.”

Somewhere, in a place between worlds and waking dreams, a fox with ember-colored fur trotted along a path made of thresholds and crossroads. Its lantern swayed, gathering stories of broken hearts and the small, brave ways they mended. And though Mara did not yet know it, her story would hang there, too, like a warm light in a window that helped guide others home.